IBD and Helminths - Detail

Helminths and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Clinical Studies

Epidemiologic evidence, case control observations, and animal studies all suggest that helminths may afford protection from or even treat intestinal inflammation. When our animal studies began to show that helminths could reduce colitis, we started exploring their potential use in IBD. There are many types of helminths, and several were judged good candidates for therapeutic application. Others have enough potential to cause disease that their application to human IBD was considered impractical at this time. After comparing many helminths, we focused on whipworm as a potential agent.

The human whipworm is Trichuris trichiura. Individuals acquire whipworm by ingesting mature eggs. The egg hatches in the small bowel, and the helminth remains confined to the intestine, residing in the right colon. Adult worms lay immature eggs that pass with the stool. Eggs require 4 to 6 weeks of incubation in moist, warm soil to mature. Because of this, the worm cannot multiply in the host or directly spread to others. Modern hygienic practices block transmission of T. trichiura.

People have had T. trichiura for eons; whipworm eggs are found in mummified remains and fossilized stools dating back more than 10,000 years.[39] Whipworm infections were common in North America and Europe before the 1940s. Although T. trichiura has become rare in these locales, it remains common in less developed tropical countries. Currently, approximately 800 million people carry whipworm, and the vast majority of these infestations are asymptomatic. However, very heavy colonization with T. trichiura can cause a dysentery-like syndrome. Trichuriasis is curable with readily available antihelminthic drugs.

Like most helminths, Trichuris sp cannot survive outside their hosts. Therefore, there is no readily available source of human whipworm. The porcine whipworm ( Trichuris suis ) is closely related to T. trichiura. T. suis can colonize in humans,[62] but such colonization is self-limited. There are no human illnesses attributed to T. suis. Importantly, T. suis eggs are available because we can obtain whipworms from pigs grown in a specific pathogen-free environment. Characteristics that make T. suis a favorable therapeutic candidate are listed in Table 2 .

Table 2

We first investigated the effect of colonization with T. suis on active IBD in a small open-label trial with four patients with CD and three with ulcerative colitis.[63**] The primary goal of the initial trial was to determine whether helminth therapy would be safe in people with intestinal inflammation. The patients ingested 2500 mature T. suis ova and were observed. The patients with CD were followed using the CD Activity Index (CDAI).[64] Three of the four patients with CD achieved remission, and the fourth had a 151-point improvement in CDAI. The patients with UC were followed using the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI).[65] All three showed improvement in SCCAI, achieving scores of 4 or less. Our conclusion was that exposure to T. suis appeared to be safe in patients with IBD. We proceeded to larger trials.

We performed a larger open-label trial testing repeated dosing of T. suis in active CD.[66] Twenty-nine patients with baseline CDAI scores between 220 and 450 entered the study. Most had disease that was refractory to standard therapy. They received 2500 T. suis ova every 3 weeks for 24 weeks. Their disease activity was monitored at weeks 12 and 24 using the CDAI. At week 12, 75.9% of the patients responded with a decrease in CDAI of 100 or more points and 65.5% achieved remission with a CDAI score less than 150. At week 24, 79.3% experienced a response and 72.4% were in remission. There were no side effects or complications attributable to T. suis colonization. This was an open-label study without a placebo arm, but it suggests that patients with CD improve with exposure to T. suis and that this helminth has a high safety profile.

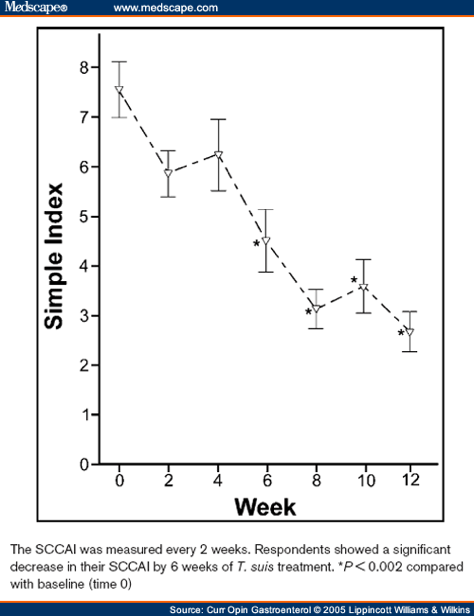

We recently published the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of T. suis in patients with UC.[67**] This trial included 54 patients with active UC as defined by a Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index (UCDAI)[68] of 4 or higher. The mean initial UCDAI of the participants was 8.7. Patients received either placebo or 2500 T. suis eggs every 2 weeks for 12 weeks. The primary end point was improvement signified by a decrease in UCDAI of 4 or more. The patients were randomly assigned: 30 to T. suis and 24 to the placebo arm. Analyzed using the intention-to-treat principle, 43.3% of the patients exposed to T. suis improved compared with 16.7% given placebo ( P < 0.04). The patients were also followed with the SCCAI. Patients given placebo showed no improvement in SCCAI, whereas patients who received T. suis had a significant decrease in scores. The SCCAI was determined every 2 weeks and permitted evaluation of time to response. The SCCAI for patients who improved by a decrease in UCDAI of 4 or more is shown in Figure 3. Patients had significant SCCAI response by week 6.

Figure 3

The study also included a crossover phase. Patients who were given placebo for the first 12 weeks were switched to T. suis for a second 12-week interval. Patients who initially received T. suis were changed to placebo. The blind was maintained. Patients with a UCDAI score of 4 or more at crossover were analyzed. In the second 12 weeks, 56.3% of the patients who received T. suis improved compared with 13.3% of patients given placebo ( P = 0.02). When the two study periods were combined, 47.8% of patients given T. suis improved compared with 15.4% of patients on placebo (Fig. 4) ( P = 0.002) as analyzed by the intention-to-treat method. If we exclude the rare patients who did not complete the study due to protocol violations, 50% of patients given T. suis improved compared with 15.8% on placebo ( P = 0.002). This study shows that helminth colonization can effectively reduce symptoms and inflammation caused by ulcerative colitis. This was the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the therapeutic use of helminths. It used a single-dose regimen. Future studies using other doses, timings, or helminths will likely show even greater efficacy.

Helminths and the Modulation of

Mucosal Inflammation

This paper was obtained from Medscape. Our understanding is that it because it was freely available that it is ok to publish it here with attribution. If this is not the case please let us know and we will remove it immediately.